|

Indian Motorcycle - May 1995

Wymond Walkem’s Service For Serious Riders

Story by Bob Tedeschi

In

the summer of 1971, Wymond Walkem was a 16-year-old kid, hanging

out in the suburbs of Toronto, and riding his Harley along side

a buddy who owned an old Chief. "I was the more mechanically

inclined of the two of us, so I ended up doing all the work,"

Walkem recalls. In

the summer of 1971, Wymond Walkem was a 16-year-old kid, hanging

out in the suburbs of Toronto, and riding his Harley along side

a buddy who owned an old Chief. "I was the more mechanically

inclined of the two of us, so I ended up doing all the work,"

Walkem recalls.

Since these were the days of Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, hip-huggers,

and (most notably) choppers, Walkem took a hacksaw to both his and

his buddy’s bikes, and, of course, raked the front end to

radical angles. And, as both motorcycles were vintage bikes with

more than their share of maintenance quirks, Walkem got to know

the inner workings of both choppers quite well. Nearly 25 years

later, Walkem has transformed the experience he gained from those

bikes into a thriving motorcycle restoration and repair business,

serving owners of vintage American bikes in his homeland (Canada),

the U.S., and abroad.

Walkem still does choppers — even Indian chopper — but

the watchword for his restorations isn’t just style. Rather,

it’s style and quality. And, if the number of Walkem's customers

is any indication, it’s a combination that is serving a substantial

market.

"We're

just knockin’ everybody dead," Walkem said of his business'

growth. "Our business has been growing ever since we opened

our doors." Of course, Walkem didn't jump into business as

a greasy-handed teenager. He paid his dues. "My first real

move into this business was going to Harley mechanic school in the

1970s," he recalls. "After that, I became a shop foreman,

and I learned more about the business end of things. Then I opened

up this shop in 1979." "We're

just knockin’ everybody dead," Walkem said of his business'

growth. "Our business has been growing ever since we opened

our doors." Of course, Walkem didn't jump into business as

a greasy-handed teenager. He paid his dues. "My first real

move into this business was going to Harley mechanic school in the

1970s," he recalls. "After that, I became a shop foreman,

and I learned more about the business end of things. Then I opened

up this shop in 1979."

Now, as then, Walkem divides his time between Harleys and Indians.

But make no mistake about which bike he favors. "The Harleys

are an easy way for me to pay the bills," he said. "But

with the Indians, what can I say? It's a labor of love, it's just

a bonus."

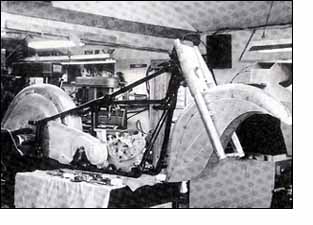

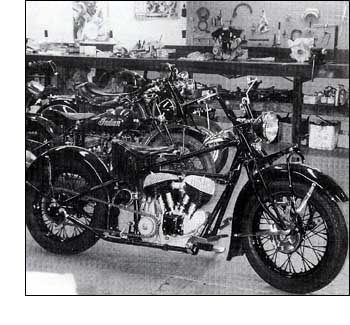

And this labor of love is more than a sidelight to his business.

Walkem's shop is full of Indians and Indian parts in various stages

of repair and restoration, and he completes about three Indian basketcase-to-roadworthy

restorations each year. The business runs with a maximum of six

full-time workers in the peak months of summer.

Walkem's

specialty, he says, is everything. "We’ve got a full

machine shop, we do milling, lathing, forging, sand-blasting, welding,

blue-printing — everything. The only thing we don't do is the

actually chroming and cad plating. But we do all the prep work for

that, even. We do the buffing — everything — so we know

it can't be screwed up." Walkem's

specialty, he says, is everything. "We’ve got a full

machine shop, we do milling, lathing, forging, sand-blasting, welding,

blue-printing — everything. The only thing we don't do is the

actually chroming and cad plating. But we do all the prep work for

that, even. We do the buffing — everything — so we know

it can't be screwed up."

I he had to boil down his business philosophy into one thought,

it would be this: "We build some serious pure Indians, but

we're interested in building road-able motorcycles more than anything,"

he says.

For instance, let's say a customer walks through Walkem's doors

with a 1946 Chief, looking for a 100-point restoration. Walkem will

do the job, but not without delivering a few words of wisdom. "I'd

try to convince him to make it as road-able as possible. So first

thing, I'd tell him to ditch the six volt system, and go to 12 volts."

Along those lines, one of Walkem's most frequent modifications

is a conversion from an Indian generator to a modern Harley generator.

"And we modify the generator housing so you have no idea it's

a different generator — it just works a hundred percent better.

Some people are throwing these VW parts into their Indians. Why

bother?"

Regardless of how you upgrade your electrics, Walkem said the important

thing is that they are modernized. "If you don't, you've got

headlights you can't see anything with, and a taillight that no

one can see you with. And one day you get rear-ended. Hey, you're

busted up, the bikes busted up. And whose fault is it? It just doesn't

make much sense to get hurt just because you're a purist."

On

the subject pf pain, Walkem is aware that it might hurt the eyes

of Indian enthusiasts to see chopped-up Chiefs rolling out of his

shop. Don't reach for the hankie quite yet, he warns. "We're

not afraid of chopping something, but we'll only do it on a bent

frame, if we find one," he said. "We don't chop any cherry

stuff. We're not stupid." On

the subject pf pain, Walkem is aware that it might hurt the eyes

of Indian enthusiasts to see chopped-up Chiefs rolling out of his

shop. Don't reach for the hankie quite yet, he warns. "We're

not afraid of chopping something, but we'll only do it on a bent

frame, if we find one," he said. "We don't chop any cherry

stuff. We're not stupid."

"And don't get me wrong. We'll do a pure restoration if a

customer wants it, no question about it," he says, laughing.

"Just don't ride with us if you can't keep up."

Most of Walkem's restorations are Chiefs of the 1940s and '50s,

although he'll also tackle the earlier models, if asked. Again,

he prefers the "newer" Chiefs because they're ones most

likely to be ridden — and ridden in a way that does honor to

the Indian marque. That is, he wants them to hit the road often,

and perform as good as (or better than) any other bike on the road.

"All the guys who work here really ride their old bikes,"

he said. "I've got a '53 Chief that I ride everywhere. Every

year, we pack up our saddlebags and head to Springfield (for "Indian

Days"). Of course we hit Cape Cod, first."

While there, and at Sturgis (he rides there, too) and other events,

Walkem runs into owners of Indians that he has restored. Walkem

said a vast majority of his customers are Canadian, but Americans

and Europeans, Australians and New Zealanders also populate his

customer list in increasing numbers. Often, these customers have

tried restorations themselves, first.

"Of course, it ends up costing them more than if they had

brought it to us in the first place, because we have to rework everything

they did wrong. Why they do it, who knows? Maybe they figure it'll

get 'em some time away from the wife and kids…"

|

|